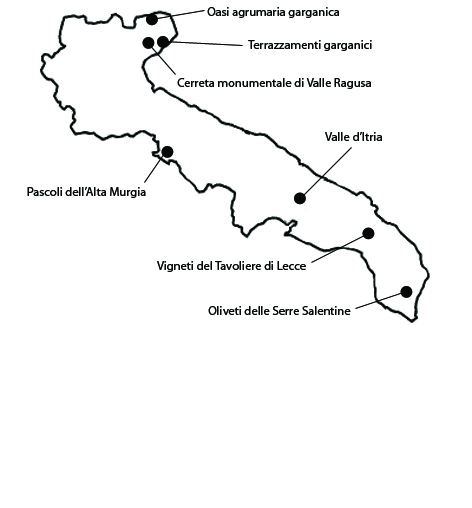

1. Monumental Turkish oak wood of Valle Ragusa

LThe monumental Turkish oak woods of Valle Ragusa extend over about 108 ha in a forest of over 5000 ha, about 378 of which are covered with Turkish oak woods. They lie in the municipality of Monte Sant’Angelo and they are included in the Gargano National Park. The area owes its significance to the historical persistence of monumental woods with very ancient origins, whose timber was used for centuries by local populations for the building of ships and railroad crossties. A number of authors of the Roman period bear witness to the antiquity of human presence in this area. The woods of Valle Ragusa feature Turkish oaks (Quercus cerris) in the dominant level and a thick understory of white hornbeam (Carpinus betulus). The Turkish oaks are of monumental sizes, often exceeding 3 m in circumference and 20 in height. Their wood is suitable for the production of planks for shipbuilding and railroad crossties, the two main economic uses it was put to in the course of history. The area is probably representative of the features of the whole Bosco Quarto until the early twentieth century, when the woods in the district underwent industrial cutting that led to age homogenization of a vast portion of the municipal territory. The area has a good degree of integrity, thanks to the presence of semi-coetaneous monumental Turkish oaks, although associated with white hornbeam and, in lesser proportion, field maple in the understory. Grazing animals help to keep the wood floor clear. As regards vulnerability, the highest risk from the point of view of conservation is the interruption of care as a result of abandonment. This is causing periodic collapses of Turkish oak trees which are then replaced by white hornbeam.

2. The citrus grove oasis in the Gargano

The citrus groves along the north coast of the Gargano promontory lie in the municipalities of Rodi Garganico, Vico del Gargano and Ischitella, in an area of 1268 ha. The area owes its significance to the historical persistence of an ancient tradition of citrus growing, certainly attested since the late Middle Ages. At this time the fruit was the melangolo or pomo citrino (bitter orange), the only variety of orange known in the Mediterranean before the introduction of the sweet orange in the second half of the 1500s. The landscape is shaped by the high-yield Gargano citrus groves screened by long masonry windbreakers with large windows, or by rows of holm oak, laurel, or evergreen pistache. As an alternative to these kinds of screens, canneti are also employed, that is, rows of dry reeds held together by transversal reeds. The local orange – more abundant than lemon – is the “biondo comune del Gargano”. Among several varieties of biondo oranges, the “Duretta del Gargano” stands out. All the local oranges have been granted PGI certification under the designation “Arancia del Gargano”. A common local lemon is the “Femminello comune”, a very old variety that is presently also PGI-certified, but there are also some very rare varieties, such as the sanguigno (blood-red) lemon. All the citrus of the Gargano are a Slow Food presidium. The citrus oasis maintained the integrity of its main components at least as late as the 1950s or 60s, and is still sufficiently preserved today.

3. Olive orchards of the Serre Salentine

The area selected as representative of the olive groves of Salento extends over 1154 ha in the municipality of Alessano, Specchia, Acquarica del Capo e Presicce. The area owes its significance not only to the historical persistence of a centuries-old crop, but also by its inclusion within a peculiar settlement fabric, a myriad of micro-settlements, mostly small rural centers. Historically regarded as the poorest and most desolate area in the Salento, today it is putting its stakes on tourism and olive oil production. The area still retains its integrity. After its depopulation, which began in the ‘50s and went on until a few years ago, today it is investing in its agricultural resources and cultural heritage, and especially on agritourism. Part of the Serre still display with more integrity than elsewhere the dominating features of the Salento rural landscape, with its especially intriguing alternation of stones and olive trees. As regards vulnerability, there are some critical factors that are worth pointing out. Notably, uncontrolled, when not outright illegal, urban expansion is degrading the landscape’s consistency and character. The intensification of agriculture has led to a reorganization of the production chain and of the historical and cultural significance of olive-growing: changes in tree spacing, modernization brought by drip irrigation, introduction of higher-yield olive-tree variants and use of chemical products and mechanical equipment. Valuable elements of the olive landscape have disappeared, such as carob trees, which used to play an important role in the diet of local peasants.

4. The pastures of the upper Murgia

The selected pasture area extends over 3146 ha on the Murgia plateau, within the municipalities of Gravina in Puglia, Spinazzola, Ruvo in Puglia e Corato. The area owes its significance to the persistence for centuries of a land management system that has given rise to a particular landscape, a result of the interaction between man and the local karstic environment. It is characterized by vast semi-natural pastures and small and sparse rural stone constructions. Shepherding has left a deep mark on the district, where the permanence of grazing grounds is associated with numerous testimonies of pastoral civilization: the area is still dotted with farmhouses and jazzi (dry-stone sheep enclosures). The landscape’s degree of integrity is still high, although this is true of not too large pasture areas that no longer form a continuous landscape, but a highly fragmented mosaic. The area’s principal vulnerability factor is connected to pasture management. Pastures in pseudo-steppes are secondary formations derived from continuously occurring disturbing factors – notably fires and grazing – which over time curb the natural dynamism of the vegetation. A prolonged absence of such factors in our area would thus favor the reversion to the natural vegetation that thrives in the local climate, a deciduous thermophilic oak forest. Priority should hence be given to measures to protect pastoral activities by clearing out infesting vegetation and preserving traditional constructions (jazzi, masserie), some of which date all the way back to the late Middle Ages.

5. Terraces in the Gargano

The area features extensive terracing over a surface of 1783 ha on the southern versant of the Gargano, within the municipality of Monte Sant’Angelo. It lies within the Gargano National Park. The area owes its significance to several factors, including its imposing, monumental terraces and the exceptional scenic beauty of the steep southern versants of the Gargano. For centuries the rockiness of the area’s soil and the steepness of its slopes forced the locals to build artificial terraces and cover the benches dug into the native rock with soil very laboriously transported up from valley deposits. Olives typically associated with almonds, are grown on the lower terraces (100-400 m a.s.l.); only almonds, due to high windiness, on the middle versants (400-600 m a.s.l.), often in association with pulses and especially cereals. The terraces extend into the outskirts of the town of Monte S. Angelo, where they are used for vegetable gardens, arables, and small vineyards. The terraces on the middle-low slopes, where olive is grown in association with almond, are still intact, even in their agronomic functionality, clearly because they still yield some income. On the contrary, the terraces on the upper slopes, once used for arables, today are prevalently in a state of abandon. They are hence exposed to renaturalization processes, which nevertheless will not avert erosion due to abandon. As regards vulnerability, the principal threat to the integrity of the terraces is failure to maintain earth retaining works as a consequence of the abandonment of the countryside and the lack of a generational turnover.

6. The Itria valley

The Valle d’Itria is one of the best known landscapes in Puglia, thanks to its characteristic trulli. The selected area extends over about 547 ha, within the municipality of Martina Franca. The area is included among UNESCO World Heritage Sites under the denomination “Trulli di Alberobello”. The most significant historical features of the Valle d’Itria’s landscape, whether rural or not, and human occupation was, at least as late as the 1950s or 60s, the fact that a significant part of the total population lived in scattered houses, and the abundance of vineyards. These occupy small, sometimes tiny plots, delimited by dry-stone walls (pareti). Each plot almost invariably has a trullo, that is, a traditional building of calcareous stone with a square plan, where peasant families lived for most or all of the year. The Val d’Itria landscape owes its integrity to the preservation, in some of its areas, of the traditional equilibrium between different soil uses, of the trulli, and of high property fragmentation. Wit the growth of high-quality specialized wine-growing, new vineyards are being planted and others are being reconverted. Farms are being reorganized and the farmhouses renovated. The most substantial threats to the landscape of the Valle d’Itria come, on the one hand, from the abandonment of some vineyards and fruit orchards as a consequence of low generational turnover among farmers; on the other, from the fact that the valley’s distinctive traditional buildings are not always being adequately protected.

7. The vineyards of the Lecce Tavoliere

The wine-growing area examined here extends over 1265 ha on the west-central versant of the Tavoliere di Lecce, in the municipalities of Salice Salentino, Guagnano e Veglie. Over the centuries, local populations transformed what was originally a harsh environment, with stagnant waters and rocky terrain. The most salient feature, even today, of the west-central part of the Tavoliere is viticulture, one of the most modern and innovative sectors of the farming economy of Salento, usually carried out on small plots, as it traditionally was. The “agricultural revolution” in Salento, with the large-scale planting of vineyards, occurred in around 1870. In a short time, “a sea of vineyards” submerged thousands and thousands of hectares. The effects of the spread of viticulture over vast areas were very significant. Latifundia were parceled out, peasants improved their social status, and malaria-infested and rocky areas were reclaimed for agriculture. The most widespread variety of grapevine in the area is the negro amaro, which combined with black malvasia yields excellent red and rosé wines. The area still has a high degree of landscape integrity. It retains original features going back to the viticultural transformation that impacted a much vaster part of Salento. Some elements of vulnerability are also observable. Threats to the historical-cultural features of the local landscape are mainly the result of the strong trend towards high-quality industrial viticulture. There have been radical changes in vineyard layout. Training on espaliers or walls is replacing traditional systems, and a reduced-cycle rotation has been introduced.