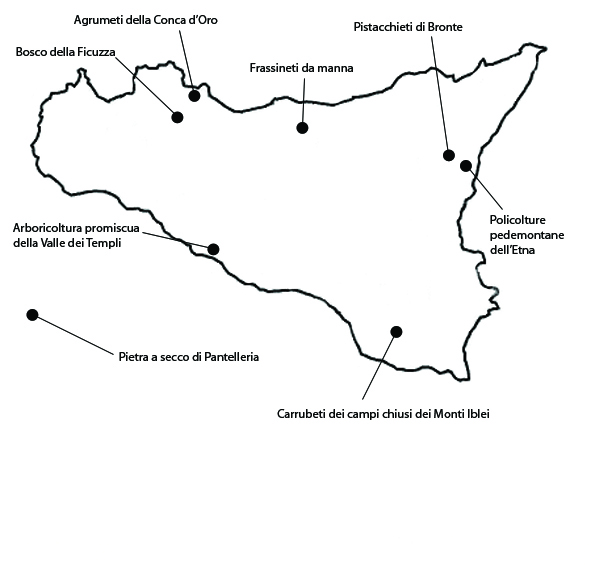

1. The citrus orchards of Conca d’Oro

IThis peri-urban citrus-growing landscape extends over 792 ha in the easternmost part of the municipality of Palermo.The area owes its significance to the historical persistence of citrus growing in the Palermo area, which dates all the way back to the Arab domination. Until the middle of the last century, the citrus orchards made the plain around Palermo appear as a single vast “garden” (giardino), as Sicilian farmers designate a fruit orchard, especially a citrus one. This is the traditional image of the Conca d’oro, “an area of ancient and almost mythical predominance of the tree”, rich in water, fertile, and blessed by a mild climate. At higher altitudes, at the foot of the calcareous mountains, the citrus trees are grown on stone terraces. Of the citrus species grown here, the most widespread is the “Tardivo di Ciaculli” tangerine, an endemic variety, not obtained by grafting or selection. It is included in the list of Traditional Agroalimentary Products of the Italian Ministry of Agricultural, Food and Forestry Policies, and also a Slow Food Presidium. On a smaller surface (20% of the total) are grown the Avana tangerine, the Ciaculli giant red medlar, lemons, and small quantities of apricots and oranges.The landscape partially owes its present integrity to the establishment in 1999 of the “Tardivo di Ciaculli” consortium, with a membership of about 90 farmers. The consortium supports small producers and collaborated with the town of Palermo to institute the Agricultural Park of Ciaculli, within whose territory strict building restrictions were applied.High farm-surface fragmentation increases the vulnerability of this system, as it does not allow the cutting of production costs. To this we need to add the growing pressure of urban expansion, often illegal, which threatens to irreversibly alter the qualities of this historical landscape.

2. The mixed orchards of the Valley of the Temples

The mixed orchard landscape of the Valley of the Temples extends over ca. 417 ha in the municipality of Agrigento. The area owes its significance not only to the historical importance of the Valley of the Temples, but also to the exceptional landscape in which the temples are set. Today, the Valley’s landscape is dominated by vast orchards of almond associated with olive trees, and with some carob, fig or pistachio on the less fertile or rocky soils. The tree spacing is irregular and the trees are of uneven ages. Their average density is of 60 to 150 specimens per hectare. In collaboration with the Department of Arboriculture of the University of Palermo, a Living Museum of the Almond Tree has been established in the Park, to preserve the ancient Sicilian almond varieties. The combination of archaeology and agricultural landscape and the early winter flowering of the almond trees make this one of the most significant landscapes in the Mediterranean, a true summa of the Mediterranean’s peculiar historical, naturalistic, and cultural traits. The Park’s activity has drastically reduced the threat of previously recurrent episodes of uncontrolled building. The area has thus managed to retain its principal agricultural features, partly thanks to the planting of new trees, although it is still crossed by incongruous, congested car roads. The vulnerability of the Valley of the Temples nevertheless remains especially high. The modern development of the city of Agrigento has betrayed the character of the old nineteenth-century city and heavily undermined the integrity of the Valley of the Temples. Furthermore, the Hill of the Temples has been impacted by serious hydrogeological problems.

3. The Ficuzza wood

The forest and silvopastoral landscape of the Royal Hunting Lodgein the woods of Ficuzza and the Cappelliere extends over 4156, within the municipalities of Corleone, Godrano, Monreale, Mezzojuso, Marineo e Piana degli Albanesi. The area owes its significance to its historical significance and the importance gained by the woods of Ficuzza in the Sicilian landscape and the Palermo area over the last two centuries. The historical origins of the present landscape can be traced back to the end of the eighteenth century. A keen hunter, the king had a hunting lodge erected here, the “Real Casina” – an exquisite building, recently restored – and transformed the area into a hunting reserve, like the many that once existed all over the Italian peninsula. The landscape is dominated by woods of deciduous and evergreen oaks (downy, holm and cork) in mixed and single-species groves, and pastures and meadows with small cultivated fields bordered by small olive groves and vineyards. Among plant species, two endemic ones are especially worthy of mention, Quercus gussonei and the Sicilian bagolaro (Celtis asperrima). The area has undergone several modifications over time, always as the result of significant human activity in the course of history. The local use of forest and pastoral resources never constituted a threat to the landscape’s integrity. However, while until recently the silvopastoral use of local resources remained sustainable and judicious, over the last few decades it has increased excessively. The main problem is overgrazing, which has compromised the traditional sustainable management of pastures and its harmonious coexistence with the evolution of the forest.

4. Enclosed fields with carob trees on the Iblei Mountains

IThe pastured carob-grove landscape of the Monti Iblei extends over 2277 ha in the municipality of Ragusa.The closed-field agrarian landscape of the southern Monti Iblei plateau owes its significance to the historical persistence of a close-knit reticule of dry-stone walls forming geometric polygons known as chiuse. Ever since the fourteenth century, when the land was granted to farmers under emphyteutic leases, the chiuse have enclose arables and monocultural or, more often, mixed orchards of olive, almond, and especially carob trees (Ceratonia siliqua). They grow in irregular patterns, with average densities of 10 to 20 trees per hectare. The low stone walls answer both the need to clear the ground of rocks and that to delimit and fence off land to allow a regular rotation of cultivation and grazing. The Castle of Donnafugata is a landmark in the area and played a central role in the organization of local agriculture.The area still retains its characteristic local landscape of wooded pastures and chiuse, with well-preserved terraces along the deep ravines. The integrity of the system is preserved thanks to its enduring agricultural use, based on a biennial rotation system. Fortunately the area is not exposed to major threats, other than renovations of private villas and farmhouses conducted without regard for traditional forms and materials.

5. Manna ash woods

IThe agroforestal manna ash grove landscape extends over 2592 ha in the municipalities of Pollina and Castelbuono. The area owes its significance to the uniqueness and historical importance of its ash-growing tradition, which goes back to the Arab domination. The earliest document mentioning manna in Sicily is a diploma of the bishop of Messina dating back to 1080. The growing of manna ash, however, apparently dates further back to the Arab domination (ninth-eleventh century). The growing of manna ash is very limited today, taking up only 250 ha of the district, mostly on rugged terrain regarded as less suited for more profitable crops. The ash groves (Fraxinus ornus or Fraxinus angustifolia) are mostly composed of trees of uneven ages, irregularly spaced out with an average density of 280 per hectare. The trees begin to be productive at 6-8 years of age. The ash grower, known as mannaluòru or ntaccaluòru, cuts 5-10 cm long slits (’ntacche) with a very sharp billhook through the whole thickness of the bark to the sapwood, starting 5 cm above the ground. From these slits, a purplish and bitter liquid flows out which becomes sweet and white through contact with the air and rapidly coagulates, forming a thin crystal-like layer: the manna. As soon as it oozes out of the slits, the liquid sets along the trunk, forming cannoli, or runs to the foot of the tree, forming manna in sorte. Today the “Manna delle Madonie” is a Slow Food Presidium. Most is processed to make mannite, which is used in the cosmetic and pharmaceutical industries, as well as in confectionery as a sweetener. The integrity and extension of the manna ash landscapes have been drastically reduced during the last century. Uncultivated ash groves are threatened by secondary successions as other tree and shrub species colonize them, as well as frequent fires. In some areas vineyards are replacing them. Another element of vulnerability is the risk of losing important know-how and very special traditional cultivation techniques handed down over the centuries.

6. Pantelleria “dry-stone” landscape

The area is a patchwork of traditional, non-irrigated cultivations on stone terraces on the island of Pantelleria. It extends over 897 ha, mainly privately owned. The area owes its significance to the historical persistence of terraced cultivations and the unique beauty of its landscape. As archaeological investigations have shown, large surfaces of the island were already terraced many centuries ago, bearing witness to the efforts of the island’s farmers to make up for severe environmental constraints. A singular feature of the local landscape are the so called orti panteschi (Pantellerian vegetable gardens). These are actually dry-stone buildings up to 4 m tall and with walls about 1 m thick, used as shelters for fruit trees, sometimes even a single one. These are usually citrus, which could not be grown otherwise due to their vulnerability to the wind and high water requirements. The shade, protection from the wind, and condensation of dew on the surface of the lava stones generate a microclimate allowing the trees to grow and bear fruit even in the total absence of irrigation. For the rest, the agriculture of Pantelleria has always thrived on drought-resistant species, cultivated with specific dry-farming techniques maximizing the soil’s water-retentive properties and reducing leaks along the surface by increasing seepage. The low Pantelleria grapevine, typical of the Phoenician and Greek colonies of Sicily, is grown in hollows that gather rainwater and protect the grapes from the wind. The olives are pruned to make them assume collapsed shapes with their branches resting on the ground, and thereby maximize the protection afforded by the dry-stone walls from the wind and sea air. Capers are grown, exceptionally, as monocultures on often imposing terraces. The area still displays remarkable integrity, but abandonment and terraces and buildings restoration carried out without attention to the the traditional features, sometimes affect the rural landscape.

7. The pistachio orchards of Bronte

This pistachio landscape extends over 1658 ha on the lower slopes of the Etna volcano, in the municipalities of Bronte and Adrano. The landscape owes its significance to the historical persistence of pistachio growing, an heirloom of the Arab domination of the island. The pistachios are grown on the slopes of the Etna, where mixed fruit orchards and vineyards provide a strong contrast to the harsher landscape of the more or less recent lava flows. Pistachio-growing was introduced in Sicily by the Arabs, but only in the nineteenth century did it expand significantly. The local population set up an agroforestal system combining pistachio trees with other fruit-bearing trees (olive, Barbary fig, almond) and numerous shrubs and spontaneous species (broom, tree spurge, evergreen pistache, terebinth), growing on very rocky basalt terrain that could not support a more intensive agriculture. The pistachio trees are grafted onto spontaneous terebinths. The tree spacing is thus irregular, with density oscillating between 50 and 500 plants per hectare. The pistachio grove landscape is quite intact, although abandonment and renaturalization are negatively influencing its conservation. Structural and environmental factors make the Bronte pistachio landscape vulnerable. Because of the impossibility of mechanization, the cultivation costs of the Bronte pistachios are necessarily higher than elsewhere. Sales are hence diminishing as a result of competition from low-cost pistachios from Iran, Turkey, Afghanistan, Greece and South America.

8. Polycultures on the slopes of Etna

The mixed arboriculture area on the northwest slope of the Etna extends over 1038 ha in the municipalities of Maletto, Bronte and Randazzo. The area owes its significance to the permanence of a traditional agriculture with remote historical origins, based on vineyards, mixed orchards, and pistachio. These grow on terraces at higher altitudes, contrasting with the harsh lava-flow landscape. The agroforestal landscape is enhanced by dry-stone rural constructions, including low walls (chiuse) and terrace walls. This combination of crop variety and rural constructions makes for a unique traditional landscape extending all around the lower slopes of the highest volcano in Europe. Many of the local products have gained official recognition, a testimony of their distinctiveness and specificity to the area. This includes the “Etna Cherry”, awaiting PDO (Protected Designation of Origin) designation; the PDO Etna Barbary Fig; and the Etna “Tabacchiera” Peach, which is included in Slow Food’s “Ark of Taste” catalogue of heritage foods. The wines produced in the area are designated as “Etna DOC” (Controlled Origin Denomination). Many of these mixed cultural systems still display a high degree of integrity, also reflected in their high specific and structural biodiversity. The area’s principal vulnerability factor is abandonment. More recently, the institution of the Etna Regional Park has been perceived as an obstacle to the sustaining and improvement of agriculture at higher altitudes. Furthermore, at lower altitudes these landscapes are frequently being eroded by discontinuous residential urbanization, since the whole district is placed under strong anthropic pressure, being a destination for skiing, naturalistic, agroforestal, and food and wine tourism.