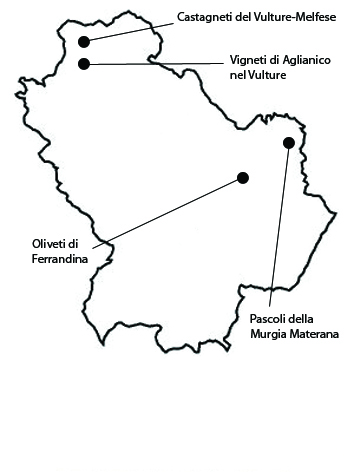

1. Chestnut groves of the Vulture-Melfi area

The area is covered with chestnut orchards extending over upper hill and lower mountain slopes for about 1637 ha, in the municipalities of Atella, Barile, Melfi, Rapolla and Rionero in Vulture. The local chestnut orchards are a highly significant landscape element of the Vulture area, especially for the Melfi farmland. They are an emblematic illustration of the expression “chestnut civilization,” used to describe the historical importance of this type of woods in Italy, where the chestnut tree is also known as the “bread tree” for the fundamental importance of its fruit in human diet. As early as 1231, the Costituzioni di Melfi included clauses to protect chestnut orchards – which at the time were mainly grown as a source of food – from damage caused by cattle. The area shows a good degree of integrity as far as the chestnut orchards are concerned, especially in the parts where regular maintenance is performed. Mount Vulture is included in the Rete Natura 2000 (Nature 2000 Network) as a Site of Community Interest and a Special Protection Zone. This approach threatens to encourage a gradual evolution towards mixed woods leading to a loss of the peculiar characteristics of the historical chestnut orchards. Further risks include intense attacks of cortical cancer on chestnut trees. Infections have indeed been reported in the area, but from a hypovirulent strain of the ascomycete Cryphonectria parasitica.

2. Pastures of the Murgia Materana

The pastures of the Murgia Materana extend over 2969 ha in a hilly area with altitudes between 200 and 520 m a.s.l., in the municipality of Matera. The Murgia Materana is distinguished from Upper Murgia not only by the singularity of its landscape, but also by human settlement going all the way back to the Paleolithic. Many testimonies of the history of the area are kept at the “Domenico Ridola” National Museum in Matera, while testimonies from the Greek period (eighth-seventh century BC) and the Roman period (third century BC onward) can be found at various sites in the area. Scholars believe that back in those times the Murgia was inhabited by shepherds and herdsmen living in small villages created by adapting small natural caves. The area also owes its archaeological significance to its many rock churches, built over a very long time span extending from the Early Middle Ages to the nineteenth century. Many fascinating rock-cut churches are found near small rural settlements or along the ancient routes connecting the town to the countryside. In these churches one recognizes architectural elements patterned after those of regular above-ground churches. The landscape shows a good degree of integrity. Possible threats to a landscape of this type could come from individual harmful actions such as illegal waste dumping, or soil tillage. The true vulnerability factor of the area is the management of the pastures of the Murgia Materana. Pastures in pseudo-steppes are secondary formations derived from disturbing factors – notably fires and grazing – which over time curbed the natural dynamism of the vegetation, allowing the present landscape to form. A prolonged absence of these factors would allow the native forest vegetation to colonize the area again, leading to the loss of the historical landscape.

3. Olive orchards of Ferrandina

The area extends over about 1395 ha in a hilly area with altitudes between 150 and 450 m a.s.l., in the municipality of Ferrandina. The district of Ferrandina owes its significance to the local importance of the olive-growing tradition, whose beginnings date back to the Great Greek period, although the area was initially colonized in the eighth century BC by the Aenotrii, who penetrated the interior of the region following river valleys. Olive trees thus strongly characterize the local landscape where the orchards alternate with arables, vegetable gardens and xerophilic woods with a prevalence of deciduous thermophilic oaks. TThe historical value of the Ferrandina olive orchards is borne out by their high number of centenary specimens. Another important aspect is that the area boasts an autochthonous cultivar, the Maieatica. The use of olives in unique cuisine recipes, deeply rooted in local tradition, such as the “Ferrandina black olives”, are a tangible testimony of the intimate connection between olive-growing and the local culture. According to local lore, oven-baked olives were part of the rations of Greek and Roman soldiers. The olive-growing district shows a good degree of integrity. Vulnerabilities are connected to the political management of the olive-growing sector. The low competitiveness of the local olive production compared to that of neighboring regions; excessive fragmentation of property; a scarcity of specialized labor; the lack of an organic development plan; the lack of a Protected Origin Denomination brand, even if Ferrandina Olives are a Slow Food Presidium and they are recognized as a Traditional Food Product by the Ministry for Agricultural, Food and ForestryPolicies.

4. Vineyards of Aglianico in the Vulture

This vineyard area extends over about 2746 ha on the foothills of the Vulture, in the municipalities of Rionero in Vulture, Barile, Rapolla, Ginestra, Ripacandida, Atella. The area owes its significance not only to the high aesthetic value of its vineyards – which harmoniously fit into an especially remarkable landscape mosaic – but especially to the fact that the Vulture is the historical district of Aglianico wine in Basilicata. The historical character of local viticulture is a strong added value for the vineyards of the Vulture area. Wine-growing in the area goes all the way back to the seventh or sixth century BC. The local vine may derive its name from Ellenico, which evolved into Aglianico in the sixteenth century, when the Kingdom of Naples was under the rule of the Aragonese. One of the main strengths of Aglianico del Vulture wine is its high quality. It is appreciated worldwide, and has recently obtained the DOCG (Controlled and Guaranteed Origin Denomination)label. From a landscape point of view, the vineyards form small patches in a heterogeneous landscape of chestnut groves, woods, olive orchards and arable land. The area shows good integrity, with espalier vineyards of variable extension harmoniously alternating with olive-orchards, family vegetable gardens, and patches of xerophilic woods on the lower slopes, and bordering on chestnut groves at higher altitudes.The most vulnerable vineyards are in the sub-mountainous area, where the lower temperatures can place a strain on the typically sub-Mediterranean local grapevine species, resulting in a longer harvesting time and a consequent lower quality of the wine. Other vulnerabilities arise from the replacing of traditional methods with modern growing and planting techniques.