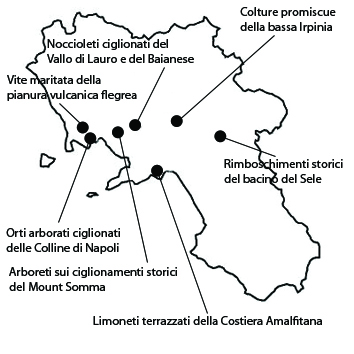

1. Historical terraced orchards on Mount Somma

The area is remarkable for its traditional apricot cultivation on terraces on the slopes of Mount Somma. It extends over a surface of 715 ha within the municipalities of Somma Vesuviana, and Ottaviano. The area owes its significance to its traditional farming methods, employing terracing systems with high agronomic, environmental and landscape value. At higher altitudes, the orchards border on chestnut coppice woods and mesophilic mixed woods with interesting relic groves of beech. The apricot orchards grow along the lower contour lines. The first certain testimony of the species’ successful cultivation in the area, dates back to the 1500s. The typical local variety of apricot is the Pellecchiella(Protected Geographical Indication), a late-maturing, vigorous and very productive tree of autochthonous origin. Overall, the area appears intact, with individual farm buildings and scattered settlements, but a generally low urban density. The terrace structure is still well defined along the slopes, although many of the terraces have been abandoned and are now covered with woods. At higher altitudes the cultivated terraces appear as isolated patches in the woods, while others extend over larger expanses along the northern slopes of the volcano. As to its vulnerability, the area, like all agricultural land in the Park of Vesuvius, is presently affected by contrasting dynamics of change. Farming is being abandoned on the higher slopes, in spite of their suitability for the growing of high-quality cultivars, while both farming and urbanization tend to intensify on the lower slopes and at the foot of the mountain. In this situation, the production of the prized Pellecchiella appears to be the only economic driving force that can ensure the vitality of the rural landscape and the costly maintenance of the historical terraces.

2. Colture promiscue della bassa Irpinia

This is a hilly mosaic landscape of about 1373 hectares characterized by multiple soil uses located in the municipalities of Taurasi, Montemiletto, Lapio, Luogosano, Sant’Angelo all’Esca, Torre Le Nocelle. The area owes its significance to the historical persistence of the typical landscapes of the Irpinian hills, which are characterized by a mosaic of different land uses: arables, orchard and vineyard gardens, olive orchards, and woods. The growing of aglianico grapes, from which Taurasi wine is produced, is mentioned by Titus Livy in the first century BC. The area shows the same structural characteristics in portions with non-specialized sparsely laid-out olive orchards and patches of woodland alternating with cultivated fields. The vineyards are cultivated according to the traditional pergola technique. Often oak and deciduous broad-leaf woods grow on hilltops, on lithic rises, and on the steeper slopes of river-cut valleys. As regards the integrity of this landscape, its agriculture is still quite vital, and its traditional organization and balances have not been completely upset by the urban transformation, as is more frequently the case in the plain. As regards vulnerability, the main concerns are for the wine-growing sector, which undoubtedly drives the local economy. This is the production area of the DOCG (Controlled and Guaranteed Origin Denomination)Taurasi wine, which today has gained international renown. Growth of demand could lead to excessive intensification threatening the traditional techniques.

3. Terraced lemon orchards of the Amalfi Coast

The area is remarkable for its citrus orchards on historical terracing along the Amalfi Coast. It extends over a surface of about 835 ha, in the municipalities of Minori, Maiori, Ravello, Atrani, Scala and Amalfi. The landscape owes its significance not just to its extraordinary beauty, but also to the historical importance of these extensive terracing systems, which have a high productive, environmental, historical, and aesthetic-perceptual value. This imposing work of environmental engineering took eight centuries, from the ducal period (twelfth century) to the early twentieth century. According to the local historian Don Giuseppe Imperato, in nearby Ravello the first seeming reference to a terraced cultivation dates back to 1012, when the Ravellans built small terraces with dry-stone walls they called macerinae. Hence the prevalence of citrus orchards and “vineyards with fruit”, with grapevines originally trained onto live supports – almond or walnut trees – later onto long poles, and finally on chestnut-pole pergolas. Thus one avoided monoculture, allowing vegetables to be grown at the foot of the trees or poles. Peasant families were thus almost totally self-sufficient for food. Within the area terrace farming still appear to be sufficiently preserved, although some abandoned terraces are being invaded by vegetation and urban expansion has encroached on what used to be a mainly rural landscape. The social cost of the decline of the landscape of the Amalfi Coast is very high, and this decline also threatens to impact the local flourishing extra-agricultural economic activities, notably tourism and seaside resort management. People involved in these sectors still fail to realize that the rural landscape is the only true base resource for the area’s economy, and that the costs of a serious landscape policy supporting historical terrace agriculture are the best possible investment for the prosperity of this world-renowned area.

4. Terraced hazelnut groves of the Vallo di Lauro and the Baiano area

This terraced hazelnut grove landscape extends over 1140 ha, within the municipality of Baiano, Mugnano del Cardinale, Sperone, Avella, Tufino. The area owes its significance to its long tradition of hazelnut growing, which indicates that Campania may have been the earliest coryliculture area in Italy. Cato, Columella, Pliny, Palladius and Virgil mention extensive growing of hazelnut, sometimes as a single crop. The hazelnut is a typical product of a millenary tradition and a strategic resource for Irpinian agriculture and economy, as even its botanical name bears out: Corylus avellana, from the ancient city of Abella. As regards integrity, the area appears quite homogeneous and well-preserved, with a very vital landscape where the terraced hazelnut groves are still clearly recognizable and have retained their function. It lies within a vaster coppice wood district with few rural structures and a sparse road system, mainly constituted of forest trails. As regards vulnerability, the area’s environment is principally threatened by the impact of production techniques on soil preservation. Weed control in hazelnut groves increases the erosive action of water runoff, resulting in high soil loss rates. It is worth remembering that these volcanic soils are not renewable, since soil losses by erosion cannot be compensated by the alteration of the carbonaceous substratum. The thinning of soils in these environments is thus an irreversible phenomenon that results in a permanent decrease of ecological productivity.

5. Terraced orchard-gardens on the hills of Naples

This area provides a typical example of a landscape with elaborately structured terraced orchard-gardens. The area lies within the district of Chiaiano in the commune of Naples, and extends for 218 hectares. The area owes its significance to the historical persistence of treed terraces. These date back to the beginning of the Angevine period (thirteenth century), but are first depicted in the Strozzi board of 1470, an oil painting in the San Martino Museum that shows a view of the city from the sea. By the late eighteenth century, arboriculture had become a significant landscape element on the hills looking out towards the Bay of Naples. The Naples Hills Park today houses about 400 ha of terraces that form the heart of this landscape. As regards its integrity, the area is still remarkably well preserved, although as an enclave within a highly urbanized zone. Over the last fifty years, this rural landscape has been impacted by intensive and chaotic building, which today has covered almost 50% of its surface and broken its continuity. Along the southern limits of the area are many yellow-tuff quarries, now abandoned. As regards its vulnerability, the fact that such a complex rural landscape lies in the heart of the vast Neapolitan metropolitan area obviously exposes it to a broad range of threats, such as the impact of extra-agricultural activities on farming and woodland ecosystems; unauthorized building; and the clandestine waste disposal cycle. On the other hand, the multi-functional propensity of the area’s agricultural and forest spaces offers the possibility to support rural development by conveying the diverse flux of environmental goods and services produced in the area to a vast public of citizens.

6. Historical afforestation in the Sele basin

The area under examination here is one where extensive afforestation and hydraulic works were carried out to protect the sources of the river Sele as part of the Puglian aqueduct project. It extends over 1958 ha, in the municipalities of Bagnoli Irpino, Nusco, Lioni. The area owes its significance to a silvopastoral landscape characterized by afforestation and hydraulic works carried out from 1903 to 1910 as part of the construction of the Puglian Aqueduct, a project that is highly representative of the State’s action to improve southern agriculture. These policies included the afforestation of about a million hectares over the whole country. Thousands of jobs were created, especially in the south. The technical objective was to ensure versant stability by recreating the forest cover. The purpose of the works carried out in the Sele basin was to increase the scarce forest cover to ensure the renewal of the water resources required to feed the Puglian Aqueduct, and also to limit the recurrent landslides and floods that plagued the area. The planted species were mostly black pine and Neapolitan alder. Today the landscape still appears essentially unaltered since 1910. The area mainly owes its vulnerability to natural evolution. Autochthonous species are replacing the planted ones and taking over open spaces, a process also favored by the gradual abandonment of grazing in the pastures.

7. Vite maritata of the Phlegraean volcanic plain

The vite maritata (married vine) landscape extends over a surface of 906 ha within the municipality of Giugliano in Campania, Villa Literno, Parete, Trentola-Ducenta, San Marcellino, Casapesenna, San Cipriano d’Aversa. This landscape mainly owes its significance to its high stands of vite maritata. According to Sereni, they are direct descendants of the Etruscan arbustum galicum. The vite maritata system consists of vines raised high up ad eventually bound to poplars. The grapevine thus takes on a typical wreath shape at the top of the high poplar. Sprays shoot out southward to limit shading to underlying crops. The result is a unique agricultural landscape. In the volcanic plain, grapevine grows to exceptional sizes, with trunks of 20-30 cm in diameter. The high quality wines produced are recognized by DOC (Controlled Origin Denomination) label: Aversa Asprinio DOC and Aversa Asprinio Alberata DOC.The integrity of this landscape has been compromised by its incorporation in the chaotic conurbation that extends today between Caserta and Naples. The effect of this model of uncontrolled urban expansion is the irreversible fragmentation of the rural space. As regards vulnerability, we must first of all observe that the vite maritata cultivation system is struggling to survive, partially due to the gradual disappearance of traditional knowledge of its specific cultivation techniques. Furthermore, the area is plagued with notorious and serious law-enforcement problems, such as unauthorized building and illegal waste management.