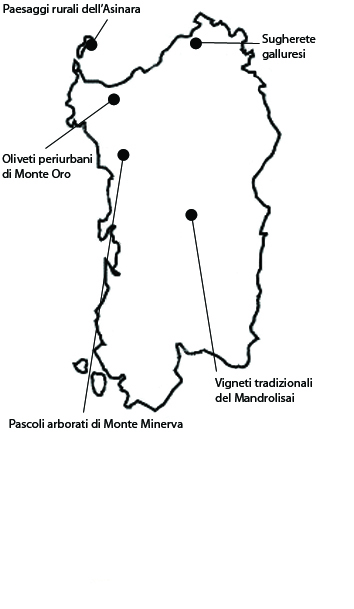

1. Per-urban olive groves of Monte Oro

The olive-growing area of Monte Oro lies within the municipality of Sassari and it extends over 1526 ha. The local landscape owes its significance to the persistence of vast, ancient olive groves on the outskirts of a middle-sized town. It thus belongs among those agricultural areas labeled “urban nodes” in the national rural development plan to highlight the special importance of cultivated areas in the proximity of towns. Ever since 1500, the Sassari olive-growing area was regarded as especially important. As a rule, olive trees are not found in the many catchment basins draining into the elaborate local torrent network, on whose fertile soil high-yield vegetable crops are grown instead. The olive-groves, mostly of the local Bosana variety, are preferably grown on shallow soil. They yield an oil designated as “Sardegna” that has earned PDO (Protected Designation of Origin) recognition. The area under consideration here is only a small part of the olive-growing system of the Sassari countryside, which extends over 4500 ha, although not continuously, having been vastly compromised by urban expansion, that in fact represent the main vulnerability.

2. Rural landscapes of the Asinara island

This area includes the rural landscapes of the island of Asinara, which extend over 1395 ha in the municipality of Porto Torres.Asinara’s rural landscape owes its significance to a very peculiar combination of factors: on the one hand to the island’s natural beauty, on the other how it was shaped by anthropic action, namely, the activities of the local agricultural penal colony. In 1885 the island’s land was expropriated for the establishment of an agricultural penal colony and a maritime quarantine station. The five hundred inhabitants of Asinara were forcibly moved out and access to the island was interdicted. Asinara remained off limits to the public from 1885 to 1999. Its total isolation was reinforced in the early 1960s, when a top security prison was established here. Level areas were tilled and hill slopes used for grazing livestock. Systematic recourse to fire modeled the landscape, and determined the characteristics of the vegetation and the soil. The most interesting area still shows evident signs of the local environment’s agrarian transformation: about 55 ha of arables for the production of fodder and about 20 of vegetable gardens and orchards. The principal activity of the island was livestock farming, as borne out by the presence of an irrigation network to allow the growing of hay in the summer and of certain vegetables. The arables are still divided into regular plots separated by dry-stone walls. The landscape still retains a good degree of integrity. Its appearance is more agricultural than natural, due to the intense use the land has undergone over the centuries. The main risk today is that the area’s state of abandon will lead to a gradual decline or disappearance of the area’s distinctive features.The closing down of the prison determined an abrupt interruption of agricultural activities, with the consequent beginning of a number of changes in the landscape. Domestic animals, no longer controlled by man, have scattered all over the island in search of space and food.

3. Planted silvo-pastoral systems of Monte Minerva

The agro-silvo-pastoral landscape of Monte Minerva extends over 1746 ha within the municipalities of Villanova Monteleone, Padria, Monteleone Rocca Doria, Romana. The area owes its significance to the fact that its landscape is still strongly marked by the agro-silvo-pastoral activities around which the local economy revolved for many centuries, until a few decades ago. It is characterized by vast treed pastures, surrounded with evergreen pistache groves and interspersed with cork and downy oak. The downy oaks still retain the shape they were given by traditional pollarding (a capitozza pruning) for fodder, a practice once widespread in the island and all over the Italian peninsula. Besides fresh forage, it also yields some firewood and, on occurrence, leafy branches for the roofing of the traditional local shelters known as pinnettas. Animal husbandry is still practiced in valley bottoms. Notably, there are some reputed horse farms here, where the animals are in part fed by grazing. The main threat to the local landscape is the abandonment of traditional practices, and especially that of pollarding. As long as trees pollarded in the past remain vital, their foliage will retain its characteristic appearance, but this will be less and less recognizable as time goes by.

4. The cork oak woods of Gallura

The cork woods of Gallura lie within the municipalities of Aglientu, Luogosanto and Tempio Pausania. The cork woods of Gallura owe their significance to the persistence of a historical silvo-pastoral activity manifested in a landscape characterized by woodland pastures, stone man-made structures, and a tree species that is typical of Sardinia. The area is part of a vast district that extends over almost all of the Sardinian northeast granite block. The landscape of this district is dominated by pure or mixed cork woods interspersed with meadows and treed pastures. The cork woods are rather stable and composed of coeval clusters as a result of periodic cutting to allow wood renewal. The rest is covered by an evergreen cork and holm oak forest associated with typical maquis underbrush. The local landscape boasts a high degree of integrity. The cork woods are well preserved, especially thanks to their importance in the local economy, which is borne out by the low impact of summer fires on them. The present landscape owes its integrity, in part, to the grazing of beef cattle, originally of a local breed, but now crossed with Charolais or Limousine bulls, which are still kept roaming free within forest areas. In spite of all this, there are some elements of vulnerability, mainly determined by the general crisis that has recently struck the animal husbandry sector. The cork market seems to be going through a crisis induced by the spread of alternative and cheaper materials for stoppers and containers, since bottle stoppers for wine-making companies account for 70-80% of the income from the cork forest. Finally, cork forests are going through the same habitat modifications as other forests: fragmentation, reduction and stress.

5. The traditional vineyards of Mandrolisai

This privately owned wine-growing area is located in the municipality of Atzara, except for a very small portion in the municipality of Sorgono. It extends over 1324 ha with altitudes between 480 and 800 m a.s.l. The area owes its significance to the historical persistence of a very ancient viticultural tradition, resulting in a landscape dominated by small bush vineyards. The traditional wine-growing system is based on the dry cultivation of small vineyards, 80% of which employing the bush vine (alberello) system, while in the rest the vines are trained on low espaliersIn the selected area, plots are bounded by strips of shrubs or trees typical of the evergreen-pistache and olivastro-dominated maquis. The wine produced in the area is included in the “Mandrolisai” DOC (Controlled Origin Denomination), a blend of three grape varieties: Monica, Bovale and Cannonau. In the selected area, the landscape mosaic appears quite intact and production still retains its traditional character. As in all hill areas, local viticulture is plagued by high production and transportation costs that are not covered by the sale price of the product. Besides the three above-mentioned vintages, other, less abundant varieties of grapes are grown in the area, making it a reservoir of genetic resources.