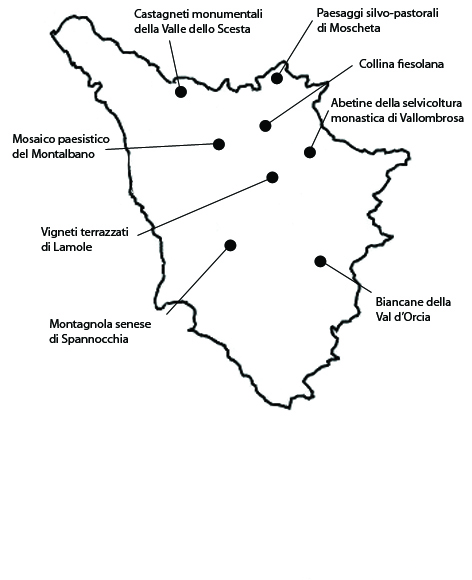

1. The fir forest of the Monastery of Vallombrosa

The historical core of the forest of Vallombrosa extends around the homonymous monastery over about 609 ha in the municipalities of Reggello and of Montemognaio, at altitudes between 700 and 1450 m a.s.l.The area owes its significance both to the historical persistence of a forest management model that supplied fir lumber for centuries and to the role of Vallombrosa in the development of forest science in Italy. The Congregation of the Vallombrosans was founded by San Giovanni Gualberto dei Visdomini, who withdrew to Vallombrosa in 1015 together with some Benedictine monks who had left the monastery of San Miniato. The landscape that developed from the sixteenth century onward, was a product of the economic interests of the monks. They started a profitable lumber trade and hence gradually replaced the beech with fir. Their management of the fir groves favored coetaneous and monospecific populations of regular rows of seedlings replacing felled trees, as part of what was known as “monastic silviculture”. The part of the woods that still retains its integrity lies around the abbey. There is a plan to preserve it by appropriate forest management practices. The remaining fir woods are evolving into mixed broadleaf woods, a phenomenon first observed in the 1980s, following the ceasing of silvicultural practices.As regards vulnerability, further abandonment of forest management would determine a spontaneous evolution of the pure-fir forest into a mixed one dominated by broadleaf species. Especially around the abbey, the conservation of the fir woods depends on the maintaining of cultivation practices based on clearcutting and replanting. Another threat to the fir woods is posed by two parasites, Armillaria mellea and Heterobasidion annosum.

2. The “white land” of Val d’Orcia

The biancane landscape described here extends over 2455 ha in the central part of the Val d’Orcia, within the municipalities of Pienza, Montepulciano, Chianciano and Sarteano. The landscape of Val d’Orcia owes its significance to the historical persistence of geological formations of great beauty set in a landscape mosaic dominated by vast bare fields, and pastures extending over gentle hills often topped by rows or single-standing cypresses. The biancane are low light-colored dome-shaped rises not exceeding ten meters in height. They occur both in isolation and in small groups and owe their color to sodium sulphate that rainfall causes to seeps into the ground and is then brought back to the surface by evaporation. Today this land yield high-quality products such as the PDO “Terre di Siena” oil, the wines Colli Senesi DOCG (Controlled and Guaranteed Origin Denomination), the Orcia DOC (Controlled Origin Denomination) and Montepulciano DOC. In spite of some changes in the crop distribution, the landscape is still dominated by its traditional bare fields, and pastures where sheep often graze. The characteristic cypresses enhance the area’s verticality. The main threat to the landscape of Val d’Orcia is building expansion, which has occurred over the last few years around small centers, but also in scattered holdings. Furthermore, the last fifty years have witnessed a simplification of forms of soil use, due not just to changes in crops but especially to damage to the olive groves caused by the frosts of 1985 and 1993. Other vulnerabilities include an excessive use of cypresses for ornamental purposes, which is indeed typical of the historical landscape of Tuscany, but on a much smaller scale.

3. The monumental chestnut groves of the Scesta valley

These monumental chestnut groves occur in a forest area extending over 2217 ha in the municipality of Bagni di Lucca. The area owes its significance to its centuries-old edible chestnut groves, with numerous monumental trees, a testimony of the importance in history of the chestnut tree as an economic resource for the populations of the Apennines. The chestnut groves alternate with coppice woods, mainly of Turkish oaks, recently converted to high stands, set in a spectacular mountain scenery. The chestnut trees often grow to exceptional sizes, with circumferences of over 9 or 10 m. Various forms of terracing and buildings connected to chestnut farming add to the landscape’s interest. The buildings include stables and chestnut-drying houses, as well as some groups of eighteenth-century buildings. The Scesta valley’s chestnut tree landscape still retains a fair degree of integrity, with rural buildings and terraces. These, however, are in an evident state of abandonment. The main threat is abandonment, as a result of which the groves are evolving into mixed woods and monumental specimens are dying through neglect and exposure to diseases. In general, the area is undergoing conspicuous reforestation processes that are undermining the landscape value of summit meadows, which apparently only periodic fires can help to preserve. As to the terraces along the versants, if they are not regularly maintained hydrogeological instability and vegetation succession can ensue.

4. Hill of Fiesole

This area extends over about 986 ha in the broader context of the southern versant of the Fiesole hills, in the municipalities of Fiesole and Florence. The area owes its significance to the historical persistence of a traditional farming landscape of exceptional beauty dotted with historical villas, extending between the towns of Florence and Fiesole. The area still retains many of the typical features of the bel paesaggio of the Tuscan hills, portrayed in innumerable pictorial and literary works. The landscape is dominated by mixed cultivations with fields combined with vineyards and especially olive and fruit trees, on regular or contour terraces. There are many farmhouses and villas. The latter feature gardens, religious buildings and tabernacles, dry-stone walls and ornamental trees such as domestic and sea pines, holm oaks and cypresses, isolated, arranged in groves, or lining the typical local white roads. While the area’s architectural heritage is still intact, its traditional farming landscapes show a lower degree of integrity. Nevertheless, this versant of the Florentine hills overall still retains an important part of the Tuscan traditional landscape. Today, historical crops survive on small plots, with a prevalence of regularly spaced olive groves. Terraces and contour terracing are still widespread. The area’s vulnerability is high. The main threat is posed by abandonment and crop simplification, which could soon set off processes of deterioration of the historical landscape, partly as a result of the loss of the water-management structures required for soil stability. The slopes need maintenance to minimize hydrogeological risk, and the traditional agricultural fabric needs to be restored.

5. The Montagnola senese of Spannocchia

The Spannocchia Farm extends over 444 ha in the municipality of Chiusdino, in the province of Siena. The farm is a significant example of the historical persistence of the agricultural landscape of the Montagnola Senese, with fields and vast wooded areas covering about 82% of its surface. The first written documents mentioning Spannocchia date back to 1225. Today the Castello di Spannocchia has become a living museum of the traditional rural life of Tuscany, where farming is conducted with great respect for the historical characteristics of the landscape. The farm retains its economic function, its main activity being the biological production of wine, oil, fruit and vegetables. The Spannocchia area still retains a high degree of landscape integrity. While independent, the Spannocchia farm is situated in an area that is undergoing constant transformation. It is thus vulnerable to land development planning, the oscillations of tourist flows, and the vagaries of the agricultural market. As in the case of wood expansion as a consequence of field or pasture abandonment, current legislation forbids the restoring of earlier soil uses, unless it is compensated by costly reforestation elsewhere; a measure that is unjustified in the case of this farm, considering the general increase of woodland everywhere and its already great extension within the farm itself. Even attempts to reintroduce grazing in woods are hindered by norms that place strong limitations on this practice for fear that it will undermine natural forest renewal.

6. Landscape mosaic of Montalbano

The agroforestal landscape of Larciano extends around the homonymous town in the province of Pistoia, for about 556 hectares. The area around the small town of Larciano is a typical example of the historical persistence of a landscape type that is often found on the hills of Tuscany, one of many variants of the terraced hills of the region. The prevalent form of cultivation is the traditional olive grove, which is found on many of the slopes. The groves often extend up all the way to the roads along the crest, and thus constitute a feature of great landscape value and highly representative of the area’s agricultural identity. Fruit trees are frequently interspersed among the olive trees. There are some vineyards in the area, too, although over very small surfaces, where the DOCG (Controlled and Guaranteed Origin Denomination) Chianti wine, subzone Montalbano, is produced. The oil is PDO-recognized as “Toscana, subzone Montalbano”. The Larciano area, in spite of some inevitable changes it shares with many of the rural communes of Tuscany, still boasts a relatively intact landscape structure. Here terracing and irrigation works, such as dry-stone walls, runnels and aqueducts, are still integrated into the road and settlement structure. The highest vulnerability issues in the area depend on the abandonment of farming, and agricultural intensification. In some parts of the area, woodland is expanding over land less suited for agriculture due to lack of exposition or acclivity. Elsewhere one remarks abandoned terraces whose dry-stone walls are in critical conditions or overrun with vegetation.

7. Silvo-pastoral landscapes of Moscheta

The silvopastoral area around the abbey of Moscheta extends over about 770 ha in the municipality of Firenzuola. The area is characterized by the historical persistence of a typical central-Apenninic landscape, dominated by beech groves, bare and treed pastures, edible chestnut groves, and important agricultural and religious structures. Moscheta is a significant example of the role of monasteries in the management of the Apenninic landscape in the first centuries of the second millennium. Part of the exquisite abbey building, now restored but deconsecrated, is still preserved, as well as part of the agricultural fabric that was already there at the time of the abbey’s foundation, including drying areas for chestnuts and many areas where charcoal was made from the local beech. A number of farms from the sharecropping period survive around the abbey, as well as monumental chestnut trees. The area is presently designated “Parco del Paesaggio Rurale Appenninico”. The park, instituted in 2007, extends over about 1000 ha. It is managed according to its own landscape plan. A small landscape museum was set up inside the abbey. The integrity of the selected landscape appears quite good. As regards vulnerability, abandonment and the ensuing increase of the woods has strongly reduced pastures and almost done away with farming, which today is only carried on by a few private individuals on small areas around rural buildings, with a few dozen grazing animals.

8. Terraced vineyards of Lamole

The area in question, located in the municipality of Greve in Chianti, extends over 700 ha. The area owes its significance not only to the historical persistence of vineyards and olive groves on terraces, but also to its landscape’s scenic beauty and the careful restoration of terraces by some landowners, who are now producing high quality wine on them. The origin of the name Lamole apparently derives from the Latin word lamulae, meaning “small blades”, strips of earth. Until sixty years ago, the agriculture of Lamole was characterized by an extreme exploitation of the entire available cultivable surface. In the ‘70s because of the spread of mechanization and the need to reduce labor, on more level ground the ritocchino (perpendicular to the slopes) planting method replaced the girapoggio method (along the contour of the hill). Since about a decade ago, the whole approach to viticulture in the area has been fully reconsidered. Many terraces have been fully restored, as has shrub vine cultivation. Now the wines produced here, besides being of great quality, have a close relationship with the quality of the landscape. The area’s integrity is high, mainly thanks to the restoration of the terraces, the persistence of polyculture, the restoration of rural buildings, and the very low rate of urbanization. Rural tourism has had a very positive impact here. In spite of ample oscillations, its growth rate has been higher than any other economic activity in the region, and in the Chianti district it plays an especially important role.