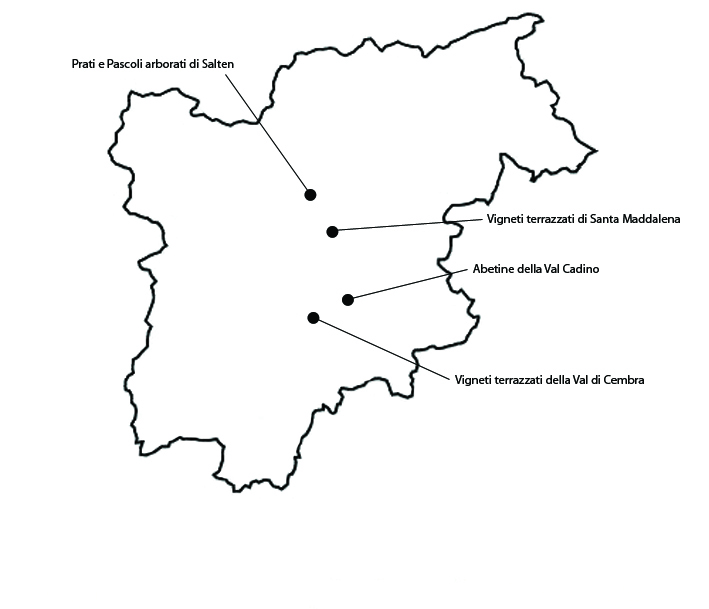

1. The meadows and wooded pastures of Salten

The area is located in the higher part of the plateau of Monzoccolo, and extends for about 2278 ha, in the municipalities of San Genesio Atesino, Meltina and Verano, in the province of Bolzano. The area is significant not solely because it is one of the largest larch covered meadows of Europe, a type of landscape that has been gradually disappearing throughout the Alps, but also to the combination of traditional historical features and splendid views of the Dolomites. The name Salten comes from the Latin saltus, which indicates a mixture of pastures, isolated trees and woods, an etymology that confirms the fact that this type of landscape dates back at least 2000 years. Another interesting feature of the area is the widespread presence of the Avelignesi horses, locally known as “Haflinger,” from the town of Hafling, a crossbreed between small mountain horses and heavier species, bred in the nineteenth century. The landscape has largely maintained its integrity. The regular mowing of the fields, albeit entirely mechanized, and the presence of grazing animals ensure the maintenance of wooded pastures and grassland. Within the area one finds rural buildings of special interest, such as thatched hay-lofts and a few mills. As for the vulnerability of the area, wooded grassland and pastures are threatened by two opposite but equally dangerous trends. On the one hand, declining revenues are leading farmers to abandon their activities, which allows woods to replace pastures and grassland. On the other, the increasing adoption of mechanized systems causes a change in mentality, so that isolated trees are increasingly seen as an annoyance and scarcely fertilized grasslands as an inefficient use of the land.

2. Terraced vineyards of Santa Maddalena

The area includes 523 ha of terraced vineyards in the small village of Santa Maddalena, in the municipality of Bolzano. The steep sunny terraces are the key to the quality of the autochthonous grapes (Schiava and Lagrein), traditionally considered among the best of Alto Adige. From these two qualities of grapes, the “Santa Maddalena” DOC (Controlled Origin Denomination)labeled wine is produced. This is where, in the Middle-Ages, the celebrated “Botzner Weine” (Bolzano wines) originated, which nowadays have been assigned the “classic” denomination label. This wine area represents one of the many instances of the Alto Adige winemaking tradition, which, while present in many parts of the region, is mostly concentrated, due to favorable climactic conditions, along the lower slopes and on the alluvial cones of the Val d’Adige. As for the integrity of the original rural landscape, the slopes where vineyards are found are still characterized by a combination of different cultivations. These are authentic niches of precious animal and vegetable biodiversity combined with historical rural structures and monuments. Fortunately the tendency to intensify cultivation is negligible, since terraced vineyards do not lend themselves to the unification of holdings. The vulnerability of the area, besides the replacement of dry-stone walls, concerns the typical cultivation system of the Alto Adige “pergola,” which risks being replaced by more modern espalier systems. As a distinctive feature of the landscape, the Alto Adige “pergolas” should be preserved, to bear witness of the traditional agricultural system, to continue to provide well-balanced habitats, characterized by high animal and vegetable biodiversity, and to support the quality of the landscape.

3. The fir and spruce woods of Val Cadino

This 2400 hectare, mainly publicly owned area includes an ample portion of the forest of Val Cadino, one of the lateral valleys of the Avisio torrent. It lies within the municipalities of Valfloriana, Castello-Molina di Fiemme, and Cavalese. The area owes its significance to the historical persistence of a landscape modeled over the centuries by forms of management based on communal ownership and focusing on timber production. The landscape thus includes timber transportation structures and sawmills. After the fall of the Roman Empire, barbarian populations overran the whole Adige valley, forcing the population to seek shelter in the neighboring valleys, including the Val di Fiemme. After a period of Lombard domination, in the year 1000 it was included in the bishopric of Trento. Around 1300 the Comunità di Fiemme was established, later renamed “Magnifica Comunità di Fiemme”. In the nineteenth century, after the French and Germanic dominations, the area came under the control of the Austro-Hungarian empire. It was returned to Italy in 1918, at the end of the Great War. From the fourteenth century onward, the valley gradually began to exploit its timber resources. To this purpose, it developed woods dominated by conifers (fir and spruce) suitable for the production of lumber, a process involving an elaborate range of activities regulated by the Comunità di Fiemme. The wooded part of the valley landscape still appears essentially intact, since the timber production is ongoing, even if timber production is no longer the driving force of the economy of the valley. The area’s vulnerability depends on the lessened importance of timber production and the uselessness of the historical structures in the current mechanized logging and timber transportation process.

4. The vineyards of Val di Cembra

The vineyard area in Val di Cembra extends over 1289 hectares within the municipalities of Cembra, Lisignago, Giovo and Trento. The area owes its significance to a landscape strongly characterized by grapevine growing, an heirloom of the Raetian civilization, based on a centuries-old manmade remodeling of the versants. The terraces supported by dry-stone walls are the valley’s most significant landscape feature. Grapevines are mainly grown employing traditional Trentine pergolas: the trunk is made to grow upwards to a height of 1.3-1.5 meters, and then the fruit-bearing branches are made to extend on a slant and transversally to the row. The result is a system of interconnected “roofs” of foliage slightly tilted up on the upslope side. An inscription praising the quality of the local wine on the “Cembra Situla” – an exquisite Etrusco-Raetian bronze basin dating back to the seventh or sixth century BC and probably used in rites in honor of Bacchus – bears witness to the early flourishing of viticulture in the area. Today the valley produces fragrant CDO-designated wines, most notably Müller Thurgau, Schiava, Nosiola, Black Pinot, and Chardonnay. The historical viticultural landscape of the Val di Cembra has retained its integrity to this day. Part of the reason for the conservation of this landscape is the fact that it produces high-quality wines and certainly not just for the local market. Furthermore, the area’s high acclivity does not allow widespread mechanization of agriculture at the expense of traditional systems. The main threat to the vineyards of the Val di Cembra is that the recurrent economic crises of viticulture may lead to an intensification of the production of porphyry.